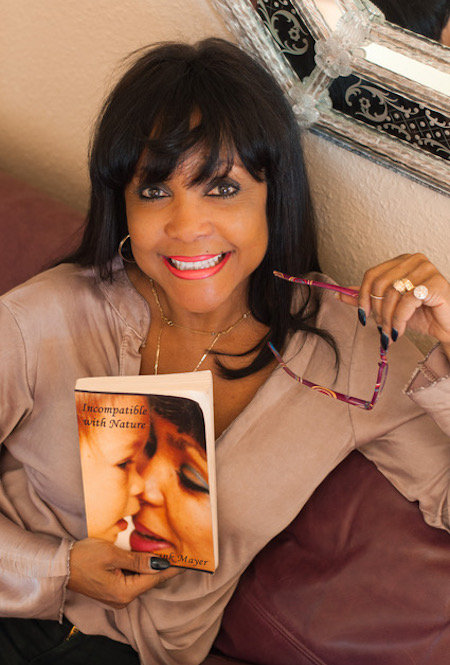

Incompatible with Nature

Awards:

"No surgery can save him," the doctor explained to my husband in German.

"Let your son die," he said to me in broken English.

This is the inspirational story of one woman's fight to save her son's life.

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Tracie Frank Mayer

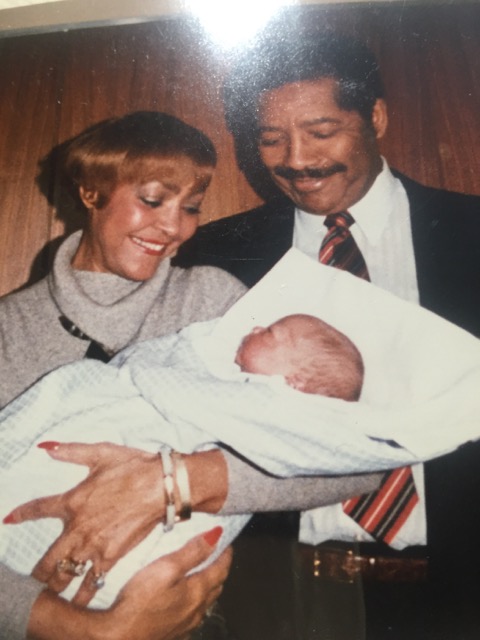

was born in Seattle, Washington, to a beauty queen and a gifted

entrepreneurial father, who courted her mother with a winning smile and the flash of

a canary yellow Cadillac.

Tracie

began working in the family real estate business at the age of nine by cleaning apartments on weekends. She has fond memories of sitting at her mother’s side in the evenings, watching her apply an assortment of creams, tonics and lotions to her face.

When

Tracie received her undergraduate degree in Business Administration from Seattle University, she had already been working in the family office full time, overseeing—along with her parents and two younger sisters—the management of nearly four-hundred rental units.

In 1983,

on a weekend jaunt to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, Tracie met her future husband, Helmut. She married him a year later. Undaunted by a language she couldn’t speak, Tracie packed her bags and moved to Cologne, Germany, Helmut’s hometown. There she gave birth to her only child, a son named Marc.

Residing in Cologne,

Germany since 1984, Tracie has worked as a writer, blogger, lyricist and public speaker.

Among her many pursuits,

Tracie supports various charitable organizations, including die Elterninitiative Herzkranker Kinder, Köln e.V. (Parents Initiative for Children with Heart Disease of Cologne), the Ronald McDonald House in Cologne, Doctors for Ethiopia and the VITA e.V. Assistenzhunde (VITA Assistant Dogs Organization).

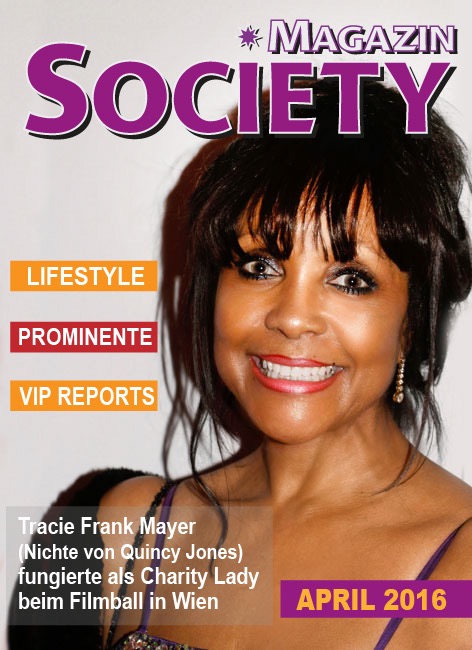

As a bi-lingual moderator,

Since March 2016, Tracie’s engagements include her work as a juror and moderator for Das Goldene Stadttor –The Golden City Gate – an internationally recognized multimedia competition at ITB, the world’s largest travel trade fair in Berlin, Germany. Tracie was a guest speaker and fund raiser on behalf of the Austrian and German Children’s Protective Agencies at the 2016 Vienna Film Ball in Austria. Since June, 2016, Tracie has served as a juror at the Miss Germany beauty pageants.

Tracie is an active member of the American International Women’s Club of Cologne,

a social organization that supports the international community in Cologne and raises funds for a variety of philanthropic projects focused on women’s rights. She is also a long time member of FAWCO (Federation of American Women’s Clubs Overseas), a United Nations recognized NGO, with a membership base of over 12,000 women from more than thirty countries. Alongside other FAWCO members, Tracie uses her moderation skills to create awareness of issues that affect women and girls around the world.

Tracie Frank Mayer loves pink, but she will wear any color.

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Incompatible with Nature

a Mothers Story

"Tracie is a hero. May many parents learn from her experience."

"This captivating memoir about a mother’s fight to save her baby's life who was born with only half of his heart in a foreign country where the mother neither knew no one, nor could speak the language, will inspire you to persevere, be determined and never give up when confronting any challenge. This is a story you will never forget!"

Dean Ornish, M.D.

Founder & President, Preventive Medicine Research Institute

Clinical Professor of Medicine, UCSF

author, The Spectrum

Dr. med. Dipl. Psych. Alex Gillor

"This story of Marc offers an example of how a determined mother never lost hope and how she pursued a worldwide search to provide the best possible options to save the life of her suffering child. I am certain this narrative will move the reader of this well written, compassionate and compelling human story."

Aldo Castañeda, M.D. Ph.D.

"A parent’s inspiring memoir, full of love, humor, and heartache. . . linguistic richness to be found throughout the text."

KIRKUS REVIEW

"Beautiful phrasing throughout. Author’s emotional recounting of this story, showing great strength in re-living it, springs from some lovely wording and visual descriptions such as bridging over their challenges. Author conveys emotion in tremendously sensory and experiential descriptions, such as roaring from the pit of her stomach. We feel her confusion, her shock, her fear, and we are hit experientially with her description of the doctor’s words as instruments of torture. Very well put. Author paints settings very well, adding sensory details that make scenes come to life, and dialogue is instilled with energy and connection. Very well done. We learn from her experience the difference between changing one’s mind and not accepting the minds of others. That’s very powerful and one of the greatest gifts of this book. Very well done. The doctor’s resistance to releasing her son to American physicians’ care moves the reader, since our hearts sink at the idea that they would be concerned with a sense of admission that they cannot handle her son’s case well enough. Author uses all caps in her reaction so well. We’re screaming alongside her. Author has crafted a moving account, one that can be of great guidance to any readers facing a similar situation. Well done. Author’s writing voice carries us confidently through some unthinkably difficult moments, yet still embraces us. "

25th Annual Writer’s Digest Self-Published Book Awards judge's commentary

"Unconditional love paired with drive and courage characterize the overwhelming life story of Marc. Through this I get energy for my work and my life."

Sonja Klima - President of the Ronald McDonald House, Austria

"Congenital heart defects are a leading cause of infant illness and death. There is certainly an urgent need for more public awareness. I wish I would have had an inspirational story to read some thirty plus years ago when my journey began. We can research facts and figures, but stories are how we learn best.

We live for inspiration.

Life is full of disappointments and none of us is immune. The improbable seems a lifetime away, but the truth is that we win some, we lose some, and sometimes we lose a lot. We struggle daily to navigate existence and regardless of the magnitude of our challenges, we seek inspirational stories of faith and hope, especially when courage is tested.

Incompatible with Nature–a Mother’s Story is a testament to the perseverance of the human spirit.

My message: Never give up!

It is my hope that Marc’s and my story will encourage you to never give up when you have to fight for something in your life–whether it be a health issue or or any other challenge! Hang in there! Be courageous in your conviction and be convinced of your courage.

To achieve our highest potential in life, sometimes we have to be fighters. So be driven. Push. Understand that character is developed in difficult times. Life is too short and too valuable to be nonchalant.

We can defy adversity. We can develop our ability to be resilient in the storm. EVERYTHING is possible because, as my daddy used to say, “It ain’t no givin’ up and no givin’ out” and that is the heart of everything!

My fight with adversity is a tale that will give hope and encouragement to anyone facing any battle not of their own choosing.

Here’s to life. Never give up!"

Tracie Frank Mayer

Read the first Chapter

Chapter 1 english

Something’s Wrong

Marc had been relatively quiet lying upon the hard flat surface of the examination table, the two snaps on his undershirt open, exposing his tender stomach and tiny chest. I was thankful the small room was warm. Having positioned my chair as close to him as possible, I sat forward on its edge, and leaning over him, gently began stroking his head, his face, his left arm and leg, as it was the left side of his body that was closest to me. I would have gobbled him up completely if I’d known it wouldn’t interrupt the examination. Comforting and reassuring him, I whispered my love to him.

“Everything’s fine, sweetheart. Yes, yes, you are Mama’s precious baby. You’re being such a good boy, yes, darling. Mommy and Papa love you. Everything’s fine, everything’s fine. Mama’s sweetie thing.”

His precious mutterings fluttered like colorful butterflies in the air. Occasionally he would wiggle or thrust his tiny legs. All the while I stroked and kissed and patted him, completely enthralled. Every time I looked at him I was overwhelmed by that “I can’t believe my baby is here in front of my eyes and I love him so much I can’t stand it!” feeling. My heart and soul burned with intense devotion to him. Watching him turn his head from time to time, I could swear he looked as if he were observing the world around him, perhaps curious about the intruder zigzagging across his chest. Thirteen days old. I wondered how large his thoughts were.

His almond eyes widened when he turned his head towards my voice, his tiny rosebud mouth open, searching for my index finger that caressed his cheek. Having become so personally acquainted with him the last thirteen days, I was well aware of his strong sucking instinct. I recalled the picture safely tucked away of him taken at twelve weeks: an ultrasound image of him floating on his back, feet in the air, his thumb in his mouth.

I had already decided before his birth that I would not use a Schnuller as a magic wand to instantly quiet his cries, or encourage his contentment. I was there for him. What on earth would he need a pacifier for? My finger, at the ready, was bent into position; it would be the smooth arch of the crook of that finger that he would welcome into his mouth. I knew that he wasn’t yet hungry, and was sure that this appeasement would help to allay any discomfort. It pleased me: mother, satisfier. Inundated with an overwhelming rush of love, I had more than a desire to nurture, protect and provide for him; I wanted to be his everything.

Though completely new to babies and their needs, I wasn’t at all nervous, in fact I felt at home with being my son’s mother. Besides the fact that God had blessed me with child, I found further reward in the absolute joy I felt when my baby was at peace, sated and content. Funny what we find gratifying at different stages of our lives.

From the moment the Professor opened his undershirt and squirted a gel on his tiny chest and began carefully sliding the scanner of the ultrasound machine back and forth in the gooey mass, he had neither fretted nor fussed. And he never cried. He mesmerized me.

Helmut sat to the left of me, his hand on my lap, his fingers every now and again lightly tapping. His touch reassured me, just as his touching me reassured him, just as I was sure my touch reassured Marc. My husband’s hand on me, my hand on our son; a chain linked by touch, by love.

We looked attentively at the scanner sliding slowly back and forth, observed it making its way under each side of our son’s neck, inching toward his chest, hesitating on the left side, then the right. It slid down toward his stomach, pausing. Up again toward his chest. Left, then right. Back and forth. Up and down. Side to side. Slowly.

The images on the monitor that the scanner produced told us nothing. It might as well have been Greek. Helmut covered my left fist with his right hand and pulled it to the folds of his lap. He held it a few moments there, tight and still. I don’t know if it was the throbbing of his pulse that I felt or mine. Soon I was aware of him unpeeling my clammy fingers and opening my hand, pressing it flat against his pant leg. He squeezed it for but a moment, patted it twice, then crowned it with his palm.

The squeeze and the pats implied that even if he were to remove his hand, I was not to remove mine. Though I couldn’t speak German and he struggled with English, we had our own language; a certain touch, look or movement spoke volumes that only we understood. I glanced at the side of his face. It immediately revealed the tension that was gnawing at the both of us.

Prior to our marriage six months earlier, that time when we each lived on different continents, the very thought of him would quicken my pulse. And in my mind’s eye, his eyes and his lips, indeed his very spirit was always smiling. His lips were now an incision in a face rigid and sober. His upper jaw jutted in and out as if he were clenching his teeth. Clenching and releasing. Clenching and releasing. I had never seen him this way and I didn’t like it. I began squirming in my seat. Why was this taking so long?

I looked expectantly at the Professor. Sitting on the opposite side of the examination table, he was within reach.

“Is this your first baby? So what brought you all the way to Germany from America? Oh, I see! Now that is true love. How long have you lived here now? Um-hmm... Well, I speak a bit of English, but I prefer of course to speak German... Is there a big difference living here compared with living in America? Which city do you come from? It is a beautiful day today, isn’t it? Don’t worry. The examination won’t hurt your son.”

Small talk that happened only in my mind. His sharply chiseled profile never cracked to emit a sound, not even a goo-goo gaga to our son. Too hard-boiled to even clear his throat, he stayed the course, continuously gliding the scanner. Removing his eyes from the monitor only long enough to check his hand position, his gaze remained fixed on the screen.

I wanted to reach out and tap him on the shoulder and ask, “Doctor, so what is it exactly that you’re looking for? How many times have you done this? Why is it taking so long? Why haven’t we been told by somebody, by – ANYBODY – why we’re here? Do all new born babies here in Germany get this examination or is this an international procedure? Is this the last stop? What is that little dot pulsating there?” But I didn’t dare. He had an impenetrable aura. Reserved. Cool as granite. Maybe it was his title that stopped me in my tracks; maybe one shouldn’t speak with the Professor unless spoken to. Perhaps it was his crisp white doctor’s coat. Out of nowhere the question of etiquette between doctor and patient popped into my mind. Is there such a thing I wondered? How does it work? Should my questions wait until the end of the exam, would it be rude to ask for an explanation during? Would it irritate? Make him angry? And then there was the language matter. I didn’t know if he understood English and if he didn’t, the resulting chopped up English and disjointed German “did I understand him” – “did she understand me” – “did I understand her” – “and he me” problem was not worth the headache. I wasn’t up to Germanic aerobics. “Just let him get on with it,” I told myself. “In a little while this will all be over. He’s going to tell you everything’s fine anyway – so just let him have his peace so he can hurry up and get finished and we can pack up and get out of here.” He never comforted me, never told me to relax, so I didn’t. I couldn’t. You see, in the back of my mind, I kept thinking, if someone is sent to a hospital he or she is sent there for a reason, but I had no clue as to why we’d been sent here. And I was absolutely certain everything was fine with our baby. So what was going on? Jesus. There were no cushions to adjust on this uncomfortable chair.

Thirty minutes had passed; a journey from the cradle to the grave. No one had said a word and I was growing wearier by the minute. Aside from Marc’s sweet murmurs and my whispers, an eerie, uncomfortable silence pervaded the room. It provided no indication of the volcano about to erupt. He continued to guide the scanner. Then, with his eyes still fixed on the monitor, his German accent thick and heavy, the Professor finally uttered, “Was ich sehe ist leider nicht gut.”

Smacking his palm to his forehead, his face twisted in pain, Helmut released an anguished sigh and slumped back in his chair. I stiffened ramrod straight in mine. An undefined feeling of fear gripped me with such force I could barely breathe. Without thinking, I snatched a fistful of Helmut’s jacket sleeve with one hand while my other clutched at Marc. My voice suddenly hoarse, as if my vocal chords had been seared, I could at first only muster a whisper.

“What did he say, Helmut?”

Though it was only a moment, it seemed a lifetime before he answered me. From where he was sitting, he could not really see the Professor’s face. I could. Leaning slightly to the right and stretching my neck to look over his shoulder, I could see that his face revealed nothing other than a stable equilibrium. A moment...Perhaps he was waiting for the Professor to say that he’d erred, that we could in fact breathe again. Perhaps he just didn’t believe his ears or thought he had misun-derstood him. The Professor continued sliding the scanner. Grating my chair against the floor, I released Helmut’s arm and grabbed his shoulder as I jumped to my feet, the chain still linked to our son. I panicked as I tried to blink away the blinding flashes of light that distorted my vision. The walls were closing in. I had to stay calm. This would all be cleared up. Trapped in a sudden heat of terror that ripped at my gut and weakened my bowels, I couldn’t have screamed if I wanted to. The dampness rising in my armpits assured me that a war was about to erupt in the heavens and it would be out of my control. I was defenseless against the “Was ich sehe ist leider nicht gut” ringing in my ears. I didn’t understand the words but Helmut’s outburst destabilized me. Scared me senseless. I could hear myself trying to breathe. I nearly tore off the leather skin of the jacket at his shoulder. Trying to keep myself under control my voice broke.

“What did he say, Helmut?”

I sensed the Professor’s eyes on me.

“Spricht Ihre Frau Deutsch?” (“Does your wife speak German?”)

Helmut shook his head. “No,” he said.

With his hand still to his forehead, his elbow now supported by the examination table, Helmut raised his free hand and groped for mine. He turned and looked up at me, tears brimmed his eyes.

He winced before he spoke and when he finally did, his voice sounded as if it belonged to someone else.

“Something’s wrong,” he whispered.

Kapitel 1 deutsch

Irgendetwas stimmt nicht

Marc lag relativ entspannt auf der harten, glatten Oberfläche des Untersuchungstisches, die zwei Druckknöpfe seines Bodys waren geöffnet, das Hemdchen hochgezogen, man sah seinen zarten Bauch und die winzige Brust. Ich war dankbar, dass es in dem kleinen Raum warm war. Ich zog meinen Stuhl so nah an ihn heran wie es nur ging, rutschte auf die Kante, beugte mich über ihn und begann, ihm zärtlich über seinen Kopf und das Gesichtchen zu streicheln, über seinen linken Arm und das linke Bein, die Teile seines Körpers, die ich am besten erreichen konnte. Ich hätte ihn am liebsten aufgefressen, mit Haut und Haaren, wenn das nicht die Untersuchung gestört hätte. So beruhigte und tröstete ich ihn, und flüsterte ihm meine Liebe zu.

“Alles wird gut, mein Schatz. Ja, ja, du bist Mamas süßes Baby. So ein lieber Junge, ja, mein Schätzchen. Mama und Papa haben Dich lieb, Alles ist gut. Mamas Süßer.”

Wie kleine bunte Schmetterlinge huschte sein zartes Babygemurmel durch den Raum. Dann und wann bewegte er sich oder strampelte mit seinen kleinen Beinchen. Die ganze Zeit über streichelte ich ihn, küsste und tätschelte ihn, völlig hingerissen. Immer, wenn ich ihn ansah, wurde ich von diesem “Ich-kann-es-gar-nicht-fassen-mein-Baby-liegt-hier-vor-mirund-ich-liebe-ihn-so-sehr-dass-ich-es-kaum-ertragen-kann” – Gefühl überwältigt. Mein Herz und meine Seele brannten vor rückhaltloser Hingabe an ihn. Ich sah zu, wie er manchmal den Kopf hin- und herbewegte, und ich hätte schwören können, dass er die Welt um ihn herum betrachtete, vielleicht neugierig, was sich da für ein Eindringling kreuz und quer über seine Brust bewegte. Dreizehn Tage alt. Was geht wohl durch seinen Kopf?

Seine Mandelaugen weiteten sich, als er den Kopf in meine Richtung wandte, meiner Stimme folgte, sein winziger Rosenknospenmund öffnete sich, suchte den Zeigefinger, mit dem ich seine Wange streichelte. Seinen starken Saugreflex hatte ich in den vergangen 13 Tagen schon sehr gut kennengelernt. Mir kam das Ultraschallbild in den Sinn, sicher verwahrt, wie er mit 12 Wochen auf dem Rücken schwebte, die Füße nach oben gereckt, den Daumen im Mund. Schon vor seiner Geburt hatte ich beschlossen, dass ich keinen Schnuller benutzen würde, dieses Zauberding, das wie auf Knopfdruck seine Schreie beruhigen, ihn in Zufriedenheit wiegen würde. Er hatte doch mich. Wofür brauchte er da einen Schnuller?

Mein Finger war schon bereit, gekrümmt, an dem glatten Knöchel würde er gleich anfangen zu nuckeln. Ich wusste, dass er noch nicht hungrig war und war mir sicher, dass dieses Friedensangebot ihm helfen würde, sich wohl zu fühlen. Das gefiel mir: die Mutter, die Quelle der Befriedigung. Überwältigt von einer Welle der Liebe, hatte ich mehr als den Wunsch ihn zu ernähren, zu beschützen und für ihn zu sorgen; ich wollte sein Ein und Alles sein.

Obwohl ich noch Neuling war was Babys und ihre Bedürfnisse angeht, war ich kein bisschen nervös, im Gegenteil, ich fühlte mich absolut wohl damit, die Mutter meines Sohnes zu sein. Abgesehen davon, dass der liebe Gott mich mit einem Kind gesegnet hatte, empfand ich die unbändige Freude, die ich spürte wenn mein Baby friedlich, satt und zufrieden war, als eine zusätzliche Belohnung. Schon komisch, was wir in den verschiedenen Phasen unseres Lebens als befriedigend empfinden.

Nicht einmal hat er gejammert, er wurde auch nicht unruhig als der Professor sein Unterhemdchen öffnete, einen Klecks Gel auf seine winzige Brust schmierte und begann, den Kopf des Ultraschalls vorsichtig durch die klebrige Masse hin und her zu schieben. Er schrie nicht ein einziges Mal. Ich war wie hypnotisiert.

Helmut saß links von mir, die Hand in meinem Schoß, ab und zu trommelte er leicht mit den Fingern. Seine Berührung beruhigte mich, so wie sie ihn selbst beruhigte, so wie meine Berührung, da war ich mir sicher, Marc beruhigte. Die Hand meines Mannes auf mir, meine Hand auf unserem Sohn, eine Kette der Berührung, der Liebe.

Wir blickten aufmerksam auf den Ultraschallkopf, der langsam hin und her glitt. Wir beobachteten, wie er methodisch an beiden Seiten zum Hals hinauf glitt, dann wieder Richtung Brust, Zentimeter für Zentimeter, und erst auf der linken und dann der rechten Seite zögerte. Der Kopf glitt wieder zum Bauch, und hielt inne. Wieder rauf zur Brust. Nach links, dann nach rechts. Hin und her. Rauf und runter. Von der einen Seite zur anderen. Langsam. Die Bilder auf dem Monitor des Ultraschallgerätes sagten uns nichts. Es hätte auch griechisch sein können. Helmut bedeckte meine linke Faust mit seiner rechten Hand und zog sie in seinen Schoß. Er hielt meine Hand ein paar Minuten lang, fest und unbewegt. Ich wusste nicht, ob es sein Pulsschlag war, den ich fühlte, oder meiner. Kurz darauf bemerkte ich wie er meine klammen Finger aufbog, die Hand öffnete und sie flach an sein Hosenbein drückte. Er drückte meine Hand einen Moment lang, tätschelte sie zweimal, und legte seine eigene darüber. Das Drücken und Tätscheln sollte wohl bedeuten dass, selbst wenn er seine Hand wegnähme, meine liegenbleiben sollte. Obwohl ich kein Deutsch sprach und er sich mit Englisch schwer tat, hatten wir unsere eigene Sprache; eine gewisse Berührung, ein Blick oder eine Bewegung sprachen Bände, die nur wir verstanden. Ich blickte sein Gesicht von der Seite an. Und sah augenblicklich die Anspannung, die an uns beiden nagte. Vor unserer Hochzeit vor sechs Monaten, als wir beide auf unterschiedlichen Kontinenten lebten, reichte der bloße Gedanke an ihn, mein Herz schneller schlagen zu lassen. Und vor meinem geistigen Auge lächelten seine Lippen und seine Augen beständig, ja, sein ganzes Wesen lächelte. Jetzt bildeten seine Lippen einen harter Schnitt in einem starren und ernsten Gesicht. Sein Unterkiefer bewegte sich vor und zurück als würde er mit den Zähnen knirschen. Knirschen und entspannen. Knirschen und entspannen. So hatte ich ihn noch nie gesehen und es gefiel mir gar nicht. Ich fing an, auf meinem Stuhl herumzurutschen. Warum dauerte das nur so lang?

Erwartungsvoll blickte ich den Professor an. Er saß auf der andern Seite der Patientenliege, er war in Reichweite.

“Ist das Ihr erstes Baby? Was hat Sie den langen Weg von Amerika nach Deutschland gebracht? Oh, ich verstehe! Das ist wahre Liebe. Seit wann leben Sie nun schon hier? Umhmm… nun, ich spreche ein bisschen Englisch, aber natürlich lieber Deutsch… Ist es sehr anders hier zu leben als in Amerika? Aus welcher Stadt kommen Sie? Heute ist wirklich ein schöner Tag, oder? Machen Sie sich keine Sorgen. Die Untersuchung wird Ihrem Sohn nicht weh tun.”

Small Talk, der nur in meiner Phantasie stattfand. Ein Profil wie gemeißelt, gab er nicht einen Laut von sich, nicht mal ein Du-du-du für unseren Sohn. Zu hartgesotten sogar, um sich zu räuspern, machte er stur weiter, immer hin und her mit dem Scannerkopf. Er blickte nur kurz vom Monitor auf seine Hand um die Position zu checken, sonst bleib sein Blick rigoros auf den Bildschirm geheftet. Ich hätte gern die Hand nach ihm ausgestreckt, ihm auf die Schulter getippt und gefragt “Doktor, wonach genau suchen Sie? Wie oft haben Sie das hier schon gemacht? Warum dauert das so lange? Warum hat uns niemand - NIEMAND bisher gesagt, warum wir überhaupt hier sind? Werden alle Neugeborenen in Deutschland so untersucht, oder ist das eine irgendwas Internationales? War es das denn jetzt? Was ist der kleine pulsierende Punkt dort?”

Aber ich habe mich nicht getraut. Er war dermaßen unnahbar. Reserviert. Kühl wie Granit. Vielleicht war es sein Titel, der mich zurückhielt; vielleicht sprach man ja einen Professor nicht einfach so an. Vielleicht war es sein gestärkter weißer Arztkittel. Mir kam urplötzlich die Frage nach den Benimmregeln zwischen Arzt und Patienten in den Sinn. Ich fragte mich, ob es so etwas wohl gab? Und wie funktionierte es? Sollte ich mit meinen Frage warten, bis er mit der Untersuchung fertig war, wäre es unhöflich, zwischendrin Fragen zu stellen? Würde es ihn irritieren? Verärgern? Und dann war da noch die Frage der Verständigung. Ich wusste nicht, ob er Englisch verstand; wenn er das nicht tat, dann wäre ein Gespräch in gebrochenem Englisch und gestammeltem Deutsch nach dem Motto “hab ich ihn verstanden - hat sie mich verstanden - habe ich sie verstanden, oder er mich” der Mühe nicht wert. Nach Verrenkungen auf Deutsch war mir grad nicht. “Lass ihn einfach machen, sagte ich mir. Das ist bestimmt alles bald vorbei. Er wird dir sowieso sagen, dass alles bestens ist – also lass ihn in Ruhe arbeiten damit er endlich fertig wird und wir zusammenpacke und hier abhauen können.” Er hat mich nicht getröstet, hat mir nie gesagt ich soll mich entspannen, also tat ich das auch nicht, ich konnte es nicht. Wissen Sie, tief drinnen dachte ich natürlich, wenn jemand in ein Krankenhaus geschickt wird, dann hat das einen Grund, aber ich hatte keine Ahnung, warum man uns hierher geschickt hatte. Und ich war absolut davon überzeugt, dass mit unserem Baby alles in Ordnung war. Also, was war los? Verflixt. Nicht mal Polster zum Zurechtrücken hatte dieser unbequeme Stuhl.

30 Minuten vergingen, eine Reise von der Wiege zum Grab. Keiner hatte ein einziges Wort gesagt, und ich wurde zusehends erschöpfter. Außer Marcs süssem Gebrabbel und meinem Flüstern herrschte in dem Raum eine unheimliche, ungemütliche Stille. Es gab keinerlei Hinweis auf den Vulkan, der sich gerade anschickte auszubrechen. Der Professor bewegte weiter den Ultraschallkopf. Dann, mit den Augen noch immer fest auf den Monitor gerichtet, mit schwerem deutschen Akzent, sagte er, “Was ich sehe ist leider nicht gut.”

Das Gesicht schmerzverzerrt, schlug sich Helmut mit der offenen Hand an die Stirn, er seufzte gequält und sackte auf seinem Stuhl in sich zusammen. Ich dagegen saß stocksteif auf meinem. Ein undefinierbares Gefühl der Angst ergriff mich mit solcher Wucht, dass ich kaum atmen konnte. Ohne nachzudenken packte ich mit der einen Hand Helmut am Jackenärmel während die andere Marc festhielt. Meine Stimme war plötzlich rau, als ob meine Stimmbänder ausgetrocknet wären und es kam nur ein Flüstern heraus.

“What did he say, Helmut?”

Es war wohl nur ein Augenblick, aber es schein wie eine Ewigkeit bis er mir antwortete. Von seinem Stuhl aus konnte er nicht wirklich das Gesicht des Professors sehen.

Ich schon. Ich beugte mich etwas nach rechts, und machte einen langen Hals, um Helmut über die Schulter zu schauen, und sah in seinem Gesicht nichts als Ausgeglichenheit. Ein Moment verging….vielleicht wartete er ja darauf, dass der Professor sagen würde, er habe sich geirrt, dass wir nun wieder atmen könnten. Vielleicht hat er ja einfach seinen Ohren nicht getraut oder gedacht, er hätte ihn missverstanden. Der Professor bewegte weiter den Ultraschallkopf. Die Stuhlbeine kratzten über den Boden als ich aufsprang, Helmuts Jacke losließ und seine Schulter packte, immer noch die andere Hand auf unserem Sohn, die Kette war noch da. Ich spürte Panik aufkommen als ich versuchte, die blendenden Lichtblitze, die meinen Blick verzerrten, wegzublinken. Die Wände schienen näher zu kommen. Ich musste die Ruhe bewahren. Alles würde sich aufklären. Gepackt von einem heftigen, heissen Schwall des Grauens, das mir auf den Magen schlug und die Eingeweide zu Wasser werden lies, hätte ich nicht schreien können, selbst wenn ich gewollt hätte. Der Ausbruch von kaltem Schweiß gab mir die Gewissheit, dass jetzt vom Himmel kommend ein Krieg ausbrechen würde, und dass mir nichts und niemand helfen konnte, das zu verhindern. Ich war hilflos angesichts ”Was ich sehe ist leider nicht gut” das in meinen Ohren nachhallte. Ich verstand die Worte zwar nicht aber Helmuts Reaktion hatte mich destabilisiert. Zu Tode erschreckt. Ich konnte hören wie ich nach Luft schnappte. Ich riss beinahe den Ärmel seiner Lederjacke ab. Ich versuchte mich unter Kontrolle zu halten, aber meine Stimme versagte fast.

“What did he say, Helmut?”

Ich spürte den Blick des Professors.

“Spricht ihre Frau Deutsch?”

Helmut schüttelte den Kopf. “Nein”, sagt er.

Mit der Hand noch an seiner Stirn, den Ellenbogen auf den Untersuchungstisch gestützt, hob Helmut seine freie Hand und tastete nach meiner. Er drehte sich und blickte zu mir auf, Tränen in den Augen. Er zuckte zusammen bevor er sprach und als er dann doch den Mund öffnete, klang seine Stimme als gehörte sie jemandem anderen.

“Da ist etwas nicht in Ordnung”, flüsterte er.

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

menopausebarbees

Together with her sister Dana, who resides in Seattle, Washington, Tracie writes an

upbeat blog—menopausebarbees—about the meaning, madness, and magic of

middle age. You can visit their blog at www.menopausebarbees.com.

Let´s have a look

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Events

03/07/2019

09/09/2019 & 09/10/2019

Presenting The Golden City Gate Awards–the world's no. 1 in film- print and multimedia competition at the International Trade Fair in Berlin, Germany

Presenting A Parent’s Perspective: Incompatible with Nature-A Mother’s Story at the World Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery Conference in Dubai, UAE

07/05/2018 7pm

Introducing The RAINBOW GALA COLOGNE

Volksbühne in Cologne - Aachener Straße 5 - 50674 Köln

Entrance fee: AK 39,50 €

Link to external Website: [ Link ]

06/16/2018 7pm

Öko-Gala with Musical-Star Maren Kristin Kern

WERK III - Baumgartenstraße 20 - 89231 Neu-Ulm

Entrance fee: VVK 79,00 €

04/07/2018 1pm

Speaking at the 7. Herztreffen from the Fontan Heart Organization in Germany

Weissenhäuser Strand - SchleswigHolstein

01/31/2018

Studio Guest on Gott sei Dank

ERF TV

01/11/2018 7pm

Incompatible with Nature–A Mother’s Story presentation

Third Place Books Seward Park - 5041 Wilson Ave S - Seattle, WA 98118

Link to external Website: [ Link ]

12/13/2017

11/12/2017

10/14/2017 1pm & 3pm

Guest on the Author’s Couch of the Catholic Media Association

Frankfurt, Germany Book Fair

02/15/2017 5.30pm

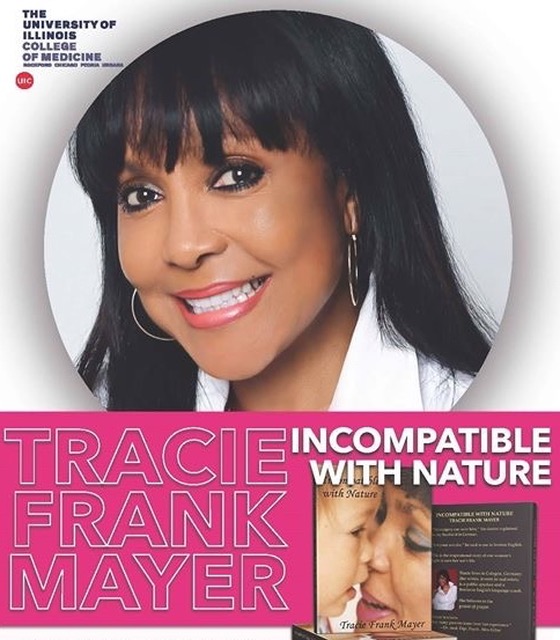

speaking at the University of Illinois College of Medicine

1601 Parkview Avenue - Rockford, Illinois

02/15/2017 11.30am

Go Red for Women’s Luncheon for the AHA

Giovanni’s Restaurant and Convention Center - 610 N. Bell School Road - Rockford, Illinois

02/11/2017 3pm

Book presentation at the Four Seasons Hotel

Beverly Hills - California

Photo: Dusty Holoubek

02/09/2017

Guest on Seattle’s King TV’s New Day NW

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Photo / Video

As of this writing, Dr. Castañeda, at eighty-six years of age, is living in Guatemala City, Guatemala where he has founded UNICARP Hospital, the first pediatric cardiac surgical care unit in the country.

This center has become the regional referral base and source of training for physicians and nurses throughout the region and currently serves children from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Belize, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

It is not unusual for Dr. Castañeda’s team to repair the hearts of many babies and children of impoverished families at no charge. Dr. Castañeda has established the Aldo Castañeda Foundation to ensure sustainability of the program.

He goes to work everyday.

If you can, please make a donation to his foundation. Make your check payable to The Friends of Dr. Aldo Castañeda Foundation. Mailing Address: Boston Children’s Hospital 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

More Pictures

Feeling like a princess!A fairy tale trip to the Vienna Film Ball in Austria would not be complete without making a visit to one of the grandest palaces of the world: Schönbrunn Palace, a former imperial summer residence. Read more about it and Vienna’s beloved empress Sissi in the menopausebarbees blogpost, Once Upon a Time (April 12, 2016)[ read more ]

Feeling like a princess!A fairy tale trip to the Vienna Film Ball in Austria would not be complete without making a visit to one of the grandest palaces of the world: Schönbrunn Palace, a former imperial summer residence. Read more about it and Vienna’s beloved empress Sissi in the menopausebarbees blogpost, Once Upon a Time (April 12, 2016)[ read more ] LEA Awards 2015This gala event recognizes the stakeholders of ‘live events’ in the music industry; namely, the managers, concert promoters and venue operators for successful shows, festivals, tours and individual events and/or outstandingly well-run locations. This industry is a pillar of the German world of music.[ read more ]

LEA Awards 2015This gala event recognizes the stakeholders of ‘live events’ in the music industry; namely, the managers, concert promoters and venue operators for successful shows, festivals, tours and individual events and/or outstandingly well-run locations. This industry is a pillar of the German world of music.[ read more ]

In other words, this is great big business. Read more about it in the blogpost at www.menopausebarbees.com, If You Want Loyalty (April 16, 2016) With the heart and soul behind the Vienna Film Ball and CEO of Global Connections, Manfred SchoedsackI had the pleasure of attending the 7th International Film Ball of Vienna which was held in the magnificent (Rathaus) City Hall in Vienna, Austria.. The glamorous event was sponsored and hosted by Mr. Manfred Schoedsack, who also generously provided airport limousine shuttles as well as overnight accommodations for his guests at the five-star PALAIS Hansen Kempinski Hotel Vienna.[ read more ]

With the heart and soul behind the Vienna Film Ball and CEO of Global Connections, Manfred SchoedsackI had the pleasure of attending the 7th International Film Ball of Vienna which was held in the magnificent (Rathaus) City Hall in Vienna, Austria.. The glamorous event was sponsored and hosted by Mr. Manfred Schoedsack, who also generously provided airport limousine shuttles as well as overnight accommodations for his guests at the five-star PALAIS Hansen Kempinski Hotel Vienna.[ read more ]

Thank you for the invitation Mr. Schoedsack! Aside from his generosity, he is also one of the kindest people you’ll ever meet.

Read more about this amazing evening in the menopausebarbees blogpost, Some Enchanted Evening (April 6, 2016) What a surprise!Thank you to William Balser, Liane Wirzberger and Alexander Feyh for this wonderful cover photo of me taken at the 2016 Vienna Film Ball. Get more news at www.society-magazin.de[ read more ]

What a surprise!Thank you to William Balser, Liane Wirzberger and Alexander Feyh for this wonderful cover photo of me taken at the 2016 Vienna Film Ball. Get more news at www.society-magazin.de[ read more ] Speaking and fundraising on behalf of the children at the 2016 Vienna Film BallGrüssgott und Servus Vienna!

Speaking and fundraising on behalf of the children at the 2016 Vienna Film BallGrüssgott und Servus Vienna!

I am honored to be here this evening.

If I may, I’d like to take a moment to ask you to consider all victims the world over, who, because of their skin color, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation or disability have faced any form of violence, humiliation, abuse or terror. We have no place in our world for this injustice, wouldn’t you agree?

A healthy world begins with our children and how they are influenced by their environments. Do they feel supported? Do they feel encouraged? Do they feel loved?

Tonight, with your generous donation to the Kinderschutzbund Österreich, you will be supporting the efforts of this wonderful organization, which was established to protect children’s rights, shield them from violence and raise them up out of poverty by supporting them with psychological, social, legal and medical counseling.

You should care about this because the children are indeed our future.There can be no better investment and who knows? One day, one of these children may have to help you in your time of need.

You – each of you, can make a difference. If you don’t have a history of giving, then there’s no better time to start than now. Your contribution can help to transform a needy child from a state of victimhood into being a person of character and a thriving member of society. You can make a direct and measurable impact on a child’s life.

Imagine that.

So in diesem Sinne, bitte ich Sie um Ihre Unterstützung.Greifen Sie tief in Ihre Taschen. Jeder Cent zählt und im Namen der Kinder, der Zukunft unsere Welt, danke ich Ihnen sehr.

Thank you very much! We’ve come a long way, my baby!Mother and son having a grand time in Barcelona, Spain August 2016. It is moments like these that make me feel life is so good that I just want to pinch myself!

We’ve come a long way, my baby!Mother and son having a grand time in Barcelona, Spain August 2016. It is moments like these that make me feel life is so good that I just want to pinch myself! Barcelona!Palm trees, good food, good people. Barcelona is the largest metropolis on the Mediterranean Sea, and it is here where I fell in love with the architectural works of Antoni Gaudí. Here I am at one of his greatest works: LaPedera. Madman or genius? You decide. Read more at menopausebarbees, Barcelona! (August 30, 2016).[ read more ]

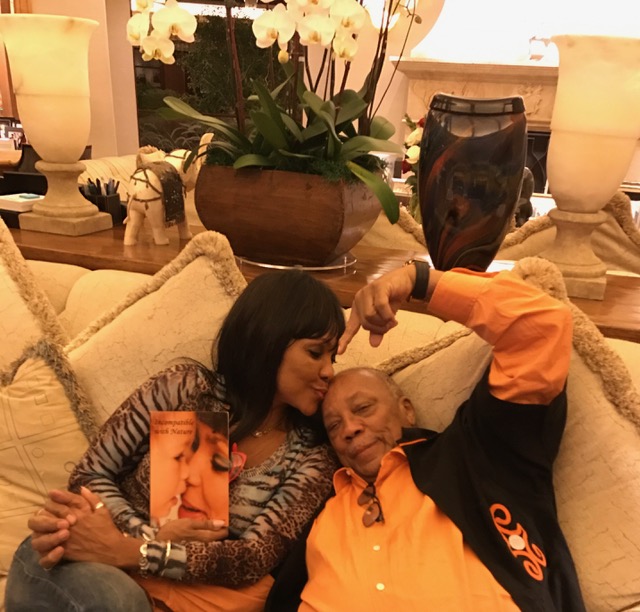

Barcelona!Palm trees, good food, good people. Barcelona is the largest metropolis on the Mediterranean Sea, and it is here where I fell in love with the architectural works of Antoni Gaudí. Here I am at one of his greatest works: LaPedera. Madman or genius? You decide. Read more at menopausebarbees, Barcelona! (August 30, 2016).[ read more ] With my son, Marc and uncle Quincy at the Montreux Jazz Festival 2016Marc and I waited along with a few others in our uncle’s dressing room before the show that first night. He entered the room, saw me and said “There’s my baby.” We all bear hugged. This man amazes me in every which way.[ read more ]

With my son, Marc and uncle Quincy at the Montreux Jazz Festival 2016Marc and I waited along with a few others in our uncle’s dressing room before the show that first night. He entered the room, saw me and said “There’s my baby.” We all bear hugged. This man amazes me in every which way.[ read more ]

After each night at the close of the show, people nearly elbowed each other to get next to him. To touch him. To say, “Quincy, remember thirty years ago when. . .” And he is patient and kind, looks you in the eye when he speaks with you, and smiles for all the pictures. . . and all the pictures and all the pictures. Read more in the menopausebarbees blogpost, The Man in Montreux (July 25, 2016). Queen Sofia!Elegant, dignified, I don’t think I’ve ever met a more refined, charming woman. Everything about her is kind: her face, her smile, her handshake, everything.[ read more ]

Queen Sofia!Elegant, dignified, I don’t think I’ve ever met a more refined, charming woman. Everything about her is kind: her face, her smile, her handshake, everything.[ read more ]

Born a princess of Greece and Denmark, her roots stem from one of the oldest royal dynasties in Europe. Her Royal Majesty Queen Sofia of Spain is the eldest daughter of King Paul I and Queen Frederica from Greece. She has three children and eight grandkids.

And she gave me a kiss on the cheek! With the one and only Harald GlööcklerI tip my hat to the creative genius of Mr. Harald Glööckler who so graciously invited me to his exclusive fashion show in the ballroom of the Hotel de Rome and his gala dinner afterwards at the Hotel Titanic in Berlin, Germany.[ visit website ]

With the one and only Harald GlööcklerI tip my hat to the creative genius of Mr. Harald Glööckler who so graciously invited me to his exclusive fashion show in the ballroom of the Hotel de Rome and his gala dinner afterwards at the Hotel Titanic in Berlin, Germany.[ visit website ]

Harald Glööckler is certainly living his life with no regrets. He is free in his mind and with his creativity and he works hard. To quote him:

“What I particularly noticed (as a child) was the fear-mongering. If you don’t play by our rules, if you don’t do what we tell you, we’ll punish you, and then you won’t be one of us any more. I didn’t want to belong in the first place…”

Please do visit his website–he’s designed something for everyone! Volunteering at the Ronald McDonald House in Cologne, Germany July 14, 2016 with Annette, Astrid und Nicola...Shortly before all the dishes had been washed and put away and the kitchen had had its final wipe down, a mother who had eaten earlier and shortly thereafter dashed back to her baby, came rushing back in saying that the cannelloni was so good, she’d love to have another serving, if that was ok. We were thrilled that we had a bit left over and could give her something to smile about because that truth remains: when we do something good for someone else, we feel good.[ read more ]

Volunteering at the Ronald McDonald House in Cologne, Germany July 14, 2016 with Annette, Astrid und Nicola...Shortly before all the dishes had been washed and put away and the kitchen had had its final wipe down, a mother who had eaten earlier and shortly thereafter dashed back to her baby, came rushing back in saying that the cannelloni was so good, she’d love to have another serving, if that was ok. We were thrilled that we had a bit left over and could give her something to smile about because that truth remains: when we do something good for someone else, we feel good.[ read more ]

There’s nothing better. It has no boundaries, no limitations. It’s a win-win. And at the end of the night, that’s a good thing.

Read more at menopausebarbees, The Ronald McDonald House in Cologne, (July 20, 2016) With Erhard Priewe and the lovely Britta Peddinghaus at the Vita Charity Gala 2016. Thank you for the invitation Mr. Priewe!Herr Priewe and his crew spared not one inch on detail. Their event design at the Kurhaus was breathtakingly amazing: the larger than life floral arrangements; the graceful tablescapes–the beverages and the banquet–from the first sip of the Fürst Von Metternich cuvée to the last bite of the peach melba à la Käfers–it was all a feast not only for the palette, but also for the eyes.[ read more ]

With Erhard Priewe and the lovely Britta Peddinghaus at the Vita Charity Gala 2016. Thank you for the invitation Mr. Priewe!Herr Priewe and his crew spared not one inch on detail. Their event design at the Kurhaus was breathtakingly amazing: the larger than life floral arrangements; the graceful tablescapes–the beverages and the banquet–from the first sip of the Fürst Von Metternich cuvée to the last bite of the peach melba à la Käfers–it was all a feast not only for the palette, but also for the eyes.[ read more ]

Read more about this event at www.menopausebarbees.com Moderating at the ITB in Berlin, film competition the Golden Citygate, the world’s number one touristic film, print and multi-media competition.My name is Tracie. I am honored to be here and on behalf of the Golden CityGate, the world’s number 1 film, print and multimedia competition, I warmly welcome all of you.[ read more ]

Moderating at the ITB in Berlin, film competition the Golden Citygate, the world’s number one touristic film, print and multi-media competition.My name is Tracie. I am honored to be here and on behalf of the Golden CityGate, the world’s number 1 film, print and multimedia competition, I warmly welcome all of you.[ read more ]

We are delighted the you’re here and as you all know, this year we are celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the ITB as well as the fifteenth anniversary of the brainchild of Mr. Wolfgang Huschert: The Golden City Gate. What began as a competition between five films from three countries 15 years ago, has ballooned into an event that has evaluated 1500 submissions from 42 countries today. This is an amazing achievement in such a short time huge and is worthy of an applause for Mr. Huschert.

This year, you award winning recipients will be taking home star trophies as a special remembrance to commemorate this fifteen year anniversary. I hope they always serve as a reminder of your stellar submissions for this event. And of course, the Diamond Award awaits the grand prize winner. All of the 128 contributions were exceptionally good this year. So good as a matter of fact, that the 40 jurors from various countries who were looking for a portrayal of creativity and emotion in the films, had to view them twice. The results tallied 1.9 awards pee country.

The President of the jury, Prof. Hagenberg suggested to Mr. Huschert to separate the point ratings nationally and internationally so that more prizes could be awarded, which is great for all you winners, but not so great for Mr. Huschert because he had to pay for all the trophies.

And with that, I would say that we are ready to begin, but before we do, I’d like to ask the winning recipients to remember to please stay a few minutes after the ceremony so that we can make a group picture. Congratulations to all of you. so, I’m excited, I’m sure you’re excited so all I have to say now is: let the awards begin.

Thank you” Girls Just Wanna Have FunWith the charming Sam Jones and friend in Berlin dressed in our Sunday best!

Girls Just Wanna Have FunWith the charming Sam Jones and friend in Berlin dressed in our Sunday best! Incompatible with Nature – A Mother’s Story in the Goody Bag - Ronald McDonald Austria Charity Gala November 2016The Ronald McDonald Austria Charity Gala November 2016 was moderated by the very charming Alfons Haider who squeezed my hand tightly as he introduced me and my book. He announced that 250 of my books would be in the take home goody-bag. There were over 500 guests in the house and I was told that there were requests for the book well after the last one was gone, which was quite an honor for me. It thrilled me to my core to see my name on the list of sponsors and supporters for this special event.

Incompatible with Nature – A Mother’s Story in the Goody Bag - Ronald McDonald Austria Charity Gala November 2016The Ronald McDonald Austria Charity Gala November 2016 was moderated by the very charming Alfons Haider who squeezed my hand tightly as he introduced me and my book. He announced that 250 of my books would be in the take home goody-bag. There were over 500 guests in the house and I was told that there were requests for the book well after the last one was gone, which was quite an honor for me. It thrilled me to my core to see my name on the list of sponsors and supporters for this special event. Every girl loves a fairytale, especially when it’s for a good cause!The circus themed charity gala for the Ronald McDonald Gala began with a cocktail reception to welcome the elegantly evening attired guests. Hors d’oeuvres, champagne and cotton candy were served by masqueraders. Great big gargantuan bunches of colorful balloons floated about. In Austria, the four Ronald McDonald houses shelter more than 900 families a year, a dream that becomes reality for many parents and their children. This particular event raised €650,000 for this cause. Priceless![ watch on youtube ]

Every girl loves a fairytale, especially when it’s for a good cause!The circus themed charity gala for the Ronald McDonald Gala began with a cocktail reception to welcome the elegantly evening attired guests. Hors d’oeuvres, champagne and cotton candy were served by masqueraders. Great big gargantuan bunches of colorful balloons floated about. In Austria, the four Ronald McDonald houses shelter more than 900 families a year, a dream that becomes reality for many parents and their children. This particular event raised €650,000 for this cause. Priceless![ watch on youtube ] Mermaids and TurtlesBeautifully made-up and coiffed mermaids were strategically placed on tables and hammocks to be voted by the dinner guests for the title of Miss Red Sea. Over four hundred votes were tallied and the title was given, but I must say that all these gorgeous gals are winners.[ read more ]

Mermaids and TurtlesBeautifully made-up and coiffed mermaids were strategically placed on tables and hammocks to be voted by the dinner guests for the title of Miss Red Sea. Over four hundred votes were tallied and the title was given, but I must say that all these gorgeous gals are winners.[ read more ]

And before the night is over, I’ll be looking at the moon and the stars in the sky, deeply inhaling the air that others thousands of years before me have inhaled.

Because…this is Egypt! Incompatible with Nature-A Mother’s Story presented at the UIC in Rockford, Illinois, February 15, 2017A highlight of my book tour in February 2017 was speaking before the University of Illinois College of Medicine. I can not thank University Dean Dr. Stagnaro-Green, his staff, the students and Mrs. Andrea Langs Bear enough for this amazing opportunity. I was so very honored because not only was my presentation open to all staff and students, it was mandatory for the second year medical students to attend. In part, I told these aspiring doctors and medical professionals to remember that words matter; that patience and communication are vital. We need to encourage and support each other for we all have the same goal and that is to save, preserve, protect and enjoy life. And I shared my father’s manifesto that he instilled upon me as a little girl and which helped/helps to lift me up and set myself in motion when I just don’t think I can go on. Grammar poor, but so very rich in content and I’m sure this was purposefully intended, it is. . .[ read more ]

Incompatible with Nature-A Mother’s Story presented at the UIC in Rockford, Illinois, February 15, 2017A highlight of my book tour in February 2017 was speaking before the University of Illinois College of Medicine. I can not thank University Dean Dr. Stagnaro-Green, his staff, the students and Mrs. Andrea Langs Bear enough for this amazing opportunity. I was so very honored because not only was my presentation open to all staff and students, it was mandatory for the second year medical students to attend. In part, I told these aspiring doctors and medical professionals to remember that words matter; that patience and communication are vital. We need to encourage and support each other for we all have the same goal and that is to save, preserve, protect and enjoy life. And I shared my father’s manifesto that he instilled upon me as a little girl and which helped/helps to lift me up and set myself in motion when I just don’t think I can go on. Grammar poor, but so very rich in content and I’m sure this was purposefully intended, it is. . .[ read more ] The Golden City Gate Multi Media AwardsMarch 9, 2017, I had once again the pleasure of introducing The Golden City Gate Multi Media Awards as well as my book, Incompatible with Nature–A Mother’s Story at the Golden City Gate Awards at the ITB, the world’s leading international travel trade show. “We humans have an innate desire to learn about the world around us…how far will you go?”[ read more ]

The Golden City Gate Multi Media AwardsMarch 9, 2017, I had once again the pleasure of introducing The Golden City Gate Multi Media Awards as well as my book, Incompatible with Nature–A Mother’s Story at the Golden City Gate Awards at the ITB, the world’s leading international travel trade show. “We humans have an innate desire to learn about the world around us…how far will you go?”[ read more ] Ronald McDonald Haus Gala am 4. NovemberIch fühle mich über die Einladung zur Ronald McDonald Haus Gala am 4. November, 2016 in Wien Österreich und der Möglichkeit mein Buch, Incompatible with Nature–a Mother's Story, dort präsentieren zu dürfen sehr geehrt! Vielen Danke Sonja Klima, Präsidentin RMD Österreich für diese großartige Einladung!

Ronald McDonald Haus Gala am 4. NovemberIch fühle mich über die Einladung zur Ronald McDonald Haus Gala am 4. November, 2016 in Wien Österreich und der Möglichkeit mein Buch, Incompatible with Nature–a Mother's Story, dort präsentieren zu dürfen sehr geehrt! Vielen Danke Sonja Klima, Präsidentin RMD Österreich für diese großartige Einladung!

So very honored to be invited to present my book, Incompatible with Nature–a Mother's Story, at the Ronald McDonald House Gala on November 4, 2016 in Vienna Austria. Thank you Sonja Klima, President of the RMD Austria for this amazing invitation!

Photo courtesy of Julia Goldsby Sonja Klima Shining in the menopausebarbee Monday Spotlight!Sometimes dreams really do come true.[ read more ]

Sonja Klima Shining in the menopausebarbee Monday Spotlight!Sometimes dreams really do come true.[ read more ]

Because of the efforts of Sonja Klima, and some very generous supporters of the Ronald McDonald House in Vienna, Austria, a very special dream will be coming true for many parents and their hospitalized babies.

Sonja Klima is one of Austria’s leading ladies. She has been president of Ronald McDonald Austria since 2010 and she is passionate about her involvement with this exceptional organisation.

Last Friday evening, November 4, 2016, she presented her 6th benefit charity gala and gala it was.

The evening was moderated by the very charming Alfons Haider who squeezed my hand tightly as he introduced me and my book. He announced that 250 of my books would be in the take home goody-bag. There were over 500 guests in the house and I was told that there were requests for the book well after the last one was gone…read more at www.menopausebarbees.com Interview on Austrian News oe24 TVThank you to Nora Kahn and the Austrian news team at oe24 for the wonderful interview featuring my book. The interview is in German–special thanks to news reporter Nadine Friedrich who warmly welcomed me and conducted an excellent interview.[ read more ]

Interview on Austrian News oe24 TVThank you to Nora Kahn and the Austrian news team at oe24 for the wonderful interview featuring my book. The interview is in German–special thanks to news reporter Nadine Friedrich who warmly welcomed me and conducted an excellent interview.[ read more ] Nothing like cuddling on the couch with the maestro!In Los Angeles for my book presentation, courtesy of and HUGE thank you to the very gracious Diane Adachi, I had the great pleasure of having a few hours of quiet time with my uncle, Quincy Jones. Each and every time I’m in his presence, I get a surge of inspiration! Understandably so, right? Read more about this spectacular evening and my thanks to all who have supported me on the first leg of my book tour in the menopausebarbees post, Incompatible with Nature-A Mother’s Story on Tour (February 20, 2017)[ read more ]

Nothing like cuddling on the couch with the maestro!In Los Angeles for my book presentation, courtesy of and HUGE thank you to the very gracious Diane Adachi, I had the great pleasure of having a few hours of quiet time with my uncle, Quincy Jones. Each and every time I’m in his presence, I get a surge of inspiration! Understandably so, right? Read more about this spectacular evening and my thanks to all who have supported me on the first leg of my book tour in the menopausebarbees post, Incompatible with Nature-A Mother’s Story on Tour (February 20, 2017)[ read more ] And another first leg book tour highlightAddressing the 400 attendees at the American Heart Association’s Go Red For Women’s Luncheon in Rockford, Illinois February 15, 2017 So carry this with you in your daily: Whether you are fighting for a life, changing course in life, or facing or enduring any kind of change, especially uncomfortable change, don’t give up! Be courageous in your conviction and have conviction in your courageousness!

And another first leg book tour highlightAddressing the 400 attendees at the American Heart Association’s Go Red For Women’s Luncheon in Rockford, Illinois February 15, 2017 So carry this with you in your daily: Whether you are fighting for a life, changing course in life, or facing or enduring any kind of change, especially uncomfortable change, don’t give up! Be courageous in your conviction and have conviction in your courageousness!

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Press / PR Inquiries

For Press / PR Inquiries contact:

Talent Exchange Ltd.

Agentur für Bühne, Film & Medien

Wapschledde 11

58644 Iserlohn

Tel.:

Fax:

Mobil:

mail:

+49 2374 – 92 36 30

+49 2374 - 93 59 92 0

+49 151 - 22 92 11 91

info@talent-x-change.de

“Look to each day for the goodness it brings,

for living life is to believe in all things.”

Tracie Frank Mayer

“Nobody has ever measured, not even poets, how much the heart can hold.”

Zelda Fitzgerald

Contact Me!

Deutsche Version